I grew up caring for animals. Always cats and dogs. Sometimes chickens and ducks. Later horses and cattle. I would feed them, make sure they had water, help build their shelters, and take care of their wounds. I hauled hay, cleaned out stalls, helped pull a calf, and doctored pink eye. Taking care of animals teaches responsibility, selflessness (chores come first), and hard work. I loved it, and I loved them.

I’ve been a little obsessed lately about what people care about and how it seems to be skewed in some odd directions. Can you make a list of things you really care about? And how do you know you really care about something? Spend time doing the work of caring? Spend money in support of the cared about thing? Give energy to the entity, relationship, or cause high on the caring list? And then, what is the outcome of your caring? That’s often even harder to identify and articulate. Certainly we gave time, money, and energy to caring for our animals—in return they gave us food, protection, fun, love, livelihood, and lessons, to name a few.

When looking up the definition of ‘care,’ I was surprised that the first meaning of the noun was ‘suffering of mind: grief.’ The second was ‘a disquieted state of mixed uncertainty, apprehension, and responsibility.’ The third was ‘painstaking or watchful attention.’ The verb care was similar. Only later on the list of meanings for both was desire, regard, interest, or fondness mentioned. The first definition actually gets to the crux of care—if what we really care about is ‘taken away,’ suffering of mind is sure to follow.

Two weeks ago we pulled out of our driveway on the Great River Road and hours later drove the Great River Road into tiny Cassville, Wisconsin. We left the Mississippi River at times to expedite our trip, but the force of it was ever present on our minds. We returned to Cassville to bury Chris’ sister’s remains beside her parents and infant brother. The four and a half months since her death had taken the edge off our grief, but our disquieted minds still desired the closure of a burial. The permanence of a burial, along with prayers and blessings for the deceased and for those caring, grieving people left to live, is a sealing of that chapter of life.

After seeing the flooding the Great River unleashed in our area, we were curious to see what was happening in Cassville at the little resort cabin we had reserved that was the favorite of Chris’ folks. The floodwaters had risen to the edge of the cabins but had started to recede by the time we got there.

Our first visitor to the deck overlooking the River was a tiny Hummingbird. Soon after, we discovered a pair of Robins had a nest in the Birch tree that provided shade from the western sunlight. The male Robin took great care to bring food to his mate who warmed the eggs in the nest they had built.

The receding floodwaters and subsequent mud provided a perfect playground for a pair of Killdeer and their fluffy, long-legged offspring. Their halting scurrying, bobbing, and distinct high-pitched chattering made them endearing neighbors.

The people-free, flooded dock was a great place for the Northern Map Turtles to bask in the sun. I didn’t even see the little ones in the bright sunlight when I was taking the photo of the big one. The next day we saw one floating down the River on a log—I think they are glad for this warm Spring weather, too!

Across the slough on an island was a dead tree that provided the perfect lookout for an ever-watchful Eagle.

It was good to be in Cassville beside the River. The cabin hadn’t changed much since the folks had stayed there, and my mind easily ‘saw’ them standing against the pine-paneled walls or on the deck overlooking the River. These people who we so deeply cared for and loved were home again or still in this River land, in this familiar cabin, and as always, in our hearts. Evening came with softly rippled reflections. The still water seemed ‘alive’ with a humming layer of mosquitoes or other bugs that had the fish jumping. The well-fed fish had little interest in the lures and bait that Chris and Aaron were throwing into the water from the marina dock.

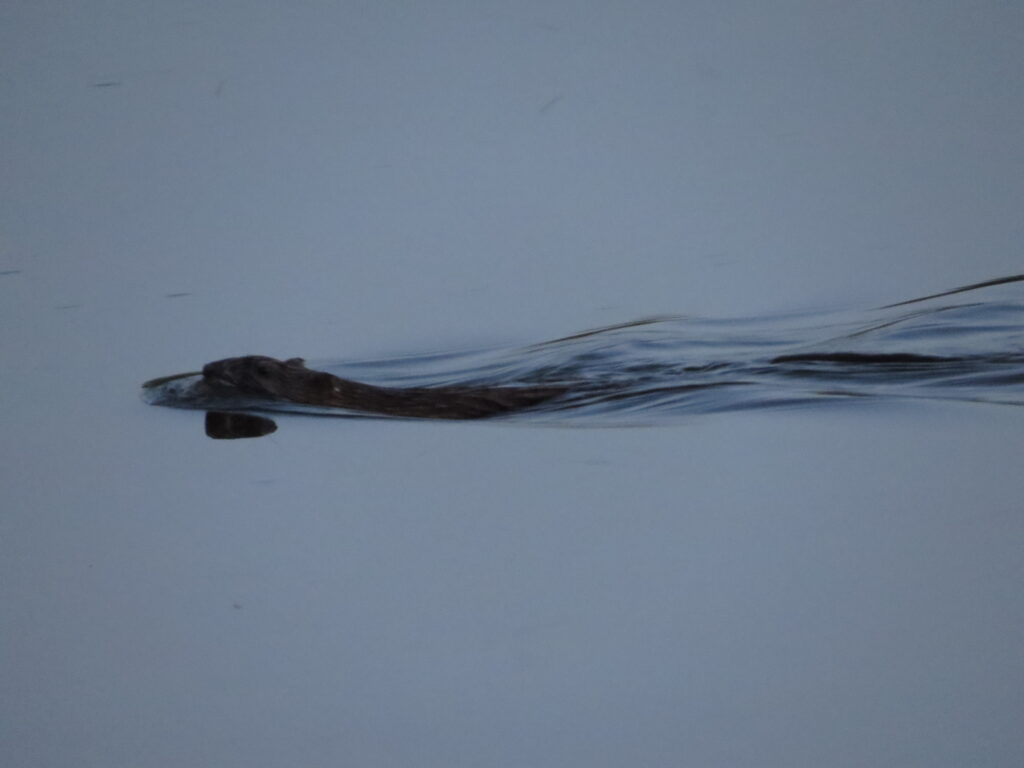

As dusk fell, a Spotted Sandpiper teetered about in the shallow water, and a beaver swam undeterred until Aaron threw his line too close for the rodent’s comfort.

I cared for our animals with diligence and love, and if one of them was injured or died, I suffered their injury or loss. I like the analogy of grief as suffering of mind—it normalizes the pain of loss and gives it a deep container and a long timeline in which to hold it. Time tends to ease a suffering mind in ways that make living a little more doable. I have learned that the next step is to give your suffering mind some watchful attention, some care, some love, so that life becomes more than just doable. If we think about our grief as a palpable display of caring and love, the grieving and the living flow together like a great river. When grief gets dammed up behind a supposedly protective wall, it can easily overwhelm everyday life. It displays as depression, anxiety, lethargy, anger, blame, hate, and violence. Remember, grief is a suffering mind, no matter the cause. I think Mary’s life and death taught me to bind the suffering with joyful living. As a person with Down Syndrome, she needed people to take care of her—there was always uncertainty, apprehension, and responsibility with her care (just as with all children.) And she cared deeply for the people around her, for animals, and for her job—she lived with joy. I can suffer her death and live with a peaceful heart. It takes time, energy, and oftentimes money to really care about someone, a relationship, an entity, or a cause. Caring is the business of lifting up, providing for, giving attention to, and suffering at the loss of the cared-for; it is not a frivolous business. We can all step into the great river of caring and grieving, loving and suffering—it is a force that can change the world.