One of the ways you know you’re on the prairie is the huge expanse of sky. Save for a lone tree or two, nothing impedes the view of the blue dome, the clouds, the sun and stars. Stretched out at your feet is a waving sea of grasses with golden seedheads, interspersed with a colorful variety of wildflowers.

On our way home from Missouri, we took old U.S. Highway 71 instead of the Interstate, and we navigated the old-fashioned way—by map. When we crossed the line from Iowa into Minnesota, I noticed a place on the map called Jeffers Petroglyphs. That sounds interesting! It was nearing seven in the evening by the time we saw the turn-off but decided to check it out anyway. Just four miles off the highway, we pulled into an almost empty parking lot. One man on a motorcycle was just getting ready to leave. He instructed us to find a booklet about the petroglyphs on a picnic table at the backside of the interpretive center, which had closed at five. We walked through the prairie grasses and flowers to a red rock ridge and began a scavenger hunt of sorts, to see and identify the rock carvings that had been cataloged in the booklet and on the signs. We stepped back in time by thousands of years!

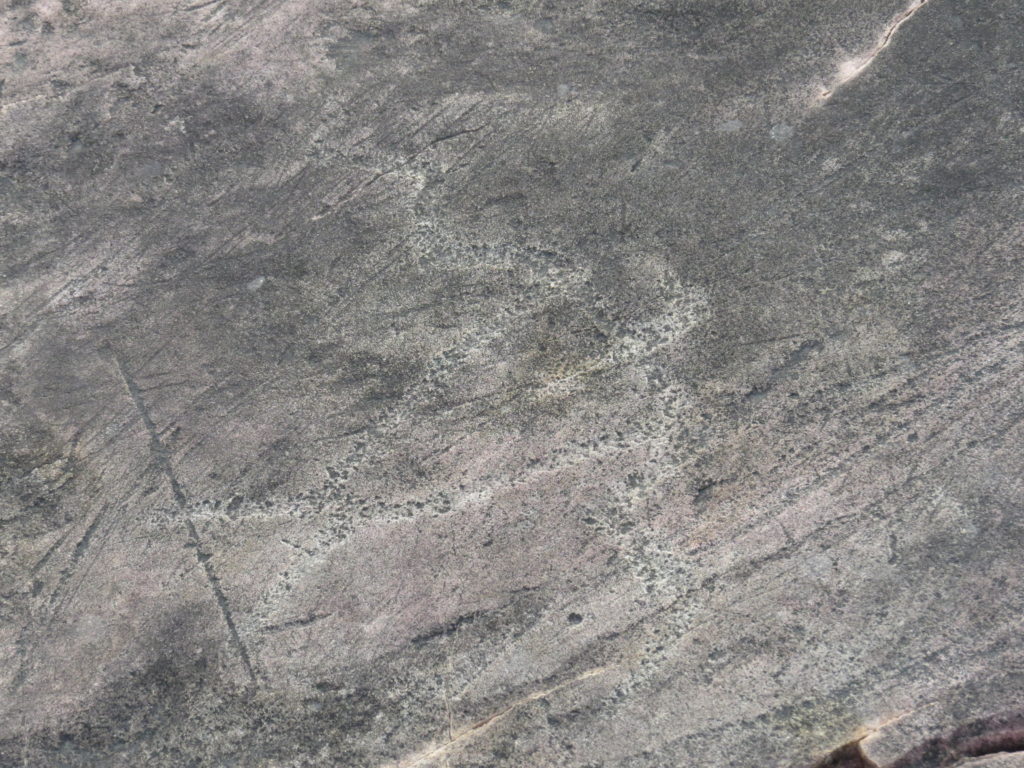

Following a roped-off pathway, at first we had a hard time seeing anything but rock. As our eyes adjusted to what the carvings looked like in texture, we began to see shapes and forms. There’s a hand print and an arrow!

Is it a bird and a buffalo?

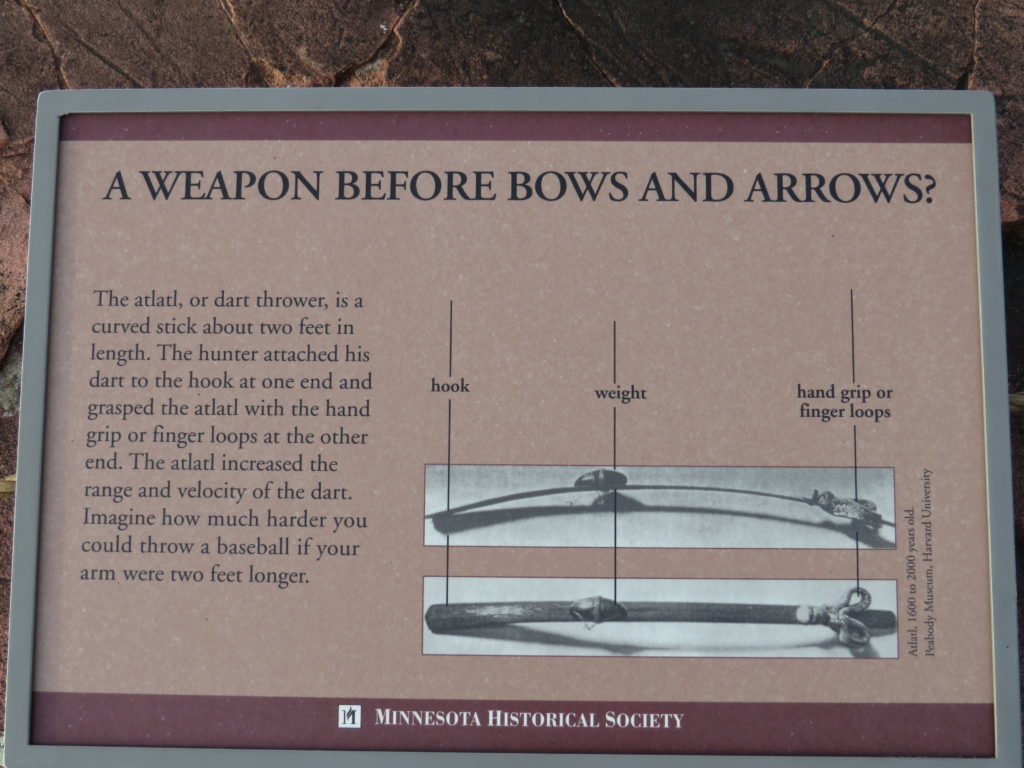

Interpretive signage told us about an ancient dart-throwing weapon used before bows and arrows called an atlatl that was used as early as 12,000 years ago. There were many carvings of atlatls, most with an exaggerated-sized stone weight on the shaft. Historians speculate that it was a ‘vision’ to increase the spiritual power that guides the hunter’s shot. Hunting, their literal livelihood, is a common theme—whether documenting actual hunts or visions of hunts to come.

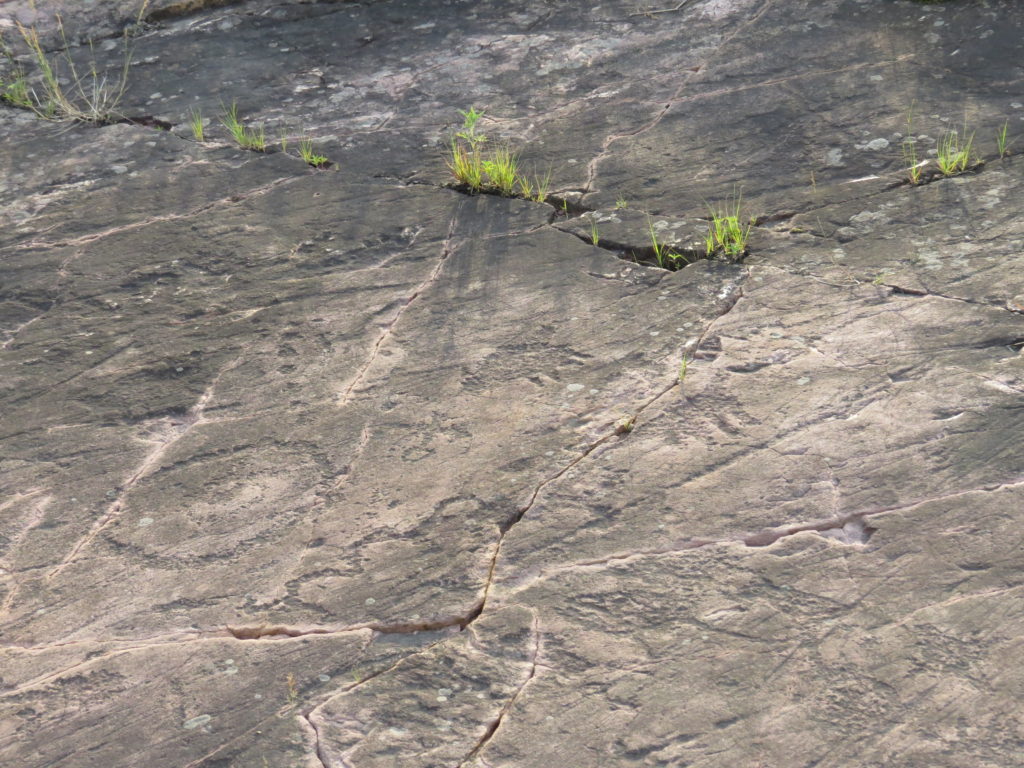

The red rock is Sioux Quartzite, the oldest bedrock formation in Minnesota, where a shallow sea deposited sand and mud for millions of years, and heat and pressure formed the metamorphic rock. It was exposed again by glaciers, wind, and water. The long scraping lines on the rock face are from the ancient moving glaciers.

In 1966, the Minnesota Historical Society purchased 40 acres to preserve this site and later added more for a total of 160 acres. It has been and still is considered to be a sacred site for Native American tribes, including Ioway, Otoe, Cheyenne, and the Dakota. Sacred ceremonies are still performed here amidst the carvings depicting the spiritual power of people and place over thousands of years. Horns or lines radiating from a head often indicates wisdom or the ability to communicate with the spirit world. The circle feet may represent a place of powerful spirits. According to the Plains Indians, the Thunderbird is a sacred spirit, giver of life and death, that can be heard as thunder as it flaps its wings and seen as lightning bolts from its eyes.

Parts of the rock face are preserved as they were 1.6 billion years ago—as sand ripples and mud flats. These interesting geological formations are a treasure that the prairie never covered up.

The carvings were done over a span of thousands of years—it is estimated the earliest were 7,000 years ago and the most recent 250 years ago. (Though there is some ‘graffiti’ by early twentieth century persons.) Another theme of the carvings were kinship ceremonies—how the bonds of kinship and social life were nurtured and strengthened. There are dozens of symbols in these next three pictures, the last, of a large carving of a woman in a shawl.

One area looked like a map, perhaps a hunting map or record of some kind of journey. Dots were carved between figures of people and other places or animals. Besides pictures of buffalo, other animals and tracks were carved in all areas of the pictographs, like birds and bear.

There are 33 acres of native prairie here, undisturbed for thousands of years. Most of the other acres have been restored to prairie. The Earth and Sky are represented in the rock carvings also. The many shapes and figures in parts of the rock face are not known—perhaps they are warriors hunting buffalo, figures of the underworld, or constellations from the starry prairie sky. Other shapes may be butterflies or dragonflies—it’s all part knowledge from the elders and historians and part imagination.

We were at the site for a little over an hour, and we were actually there at a good time, as the signage said mornings and evenings are the best time to see the carvings.

Interpretation of the carvings, along with the ongoing spiritual importance, was documented by elders from different tribes. (see MN Historical Society) Although the historical and archaeological aspects of the site were important in its preservation, it is the input from the Native Americans whose ancestors lived here that highlights the incredible significance of this place and what we can learn from it. (Italics in the following quotes are mine.)

“…and the last thing I would suggest to a visitor who wasn’t a tribal or indigenous person… somewhere back down your family tree, if you can go back far enough you’re going to find out you came from a tribal people and if you let that part of you speak… maybe you’ll find something out about yourself and your own history and your place in the world.” -Tom Ross, Dakota Elder, Upper Sioux Community Pejuhutazizi Oyate, Minnesota

“And when you walk around out there and just take your time and it’s like everything you feel is you’re walking amongst the spirit of all our people. And I know that they do enjoy our company. And the things, the signs, everything that they had left out there for us -is to remind us of who we are.” -Carrie Schommer, Upper Sioux Dakota Elder, Upper Sioux Community Pejuhutazizi Oyate, Minnesota

This site is where Minnesota’s recorded history begins, but it tells the story of the whole continent before it was named. It illustrates sacred ceremonies and important events, visions and dreams, prayers and messages, spiritual and social life. It depicts the daily substance of livelihood—the means of securing the necessities of life. It portrays the map of life’s journeys, both lived and envisioned. It demonstrates the inexplicable connection we humans have with Earth and Sky and all of Nature. It describes how imperative kinship is to our well-being and to that of our society. And finally, it illuminates that we the people—all of us, no matter our livelihood, no matter where we come from, no matter the color of our skin—are spiritual beings living in a spiritual world.