Have you ever asked yourself to see a situation from a wider perspective? Easy question to ask, but difficult, so very difficult, to actually do. I’m reading The Book of Joy—Lasting Happiness in a Changing World by His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu with Douglas Abrams. Abrams writes, “The Dalai Lama used the terms wider perspective and larger perspective. They involve stepping back, within our own mind, to look at the bigger picture and to move beyond our limited self-awareness and our limited self-interest. Every situation we confront in life comes from the convergence of many contributing factors….When we confront a challenge, we often react to the situation with fear and anger. The stress can make it hard for us to step back and see other perspectives and other solutions….We (can) see that in the most seemingly limiting circumstance we have choice and freedom, even if that freedom is ultimately the attitude we will take.” Fear and stress, anger and limiting circumstances sound very familiar to all of us, all of a sudden, in this changing world.

I’ve always appreciated a ‘big picture’ approach, but only on the basis of a multitude of information from many small observations and facts (science). The big picture requires us to look beyond what we see (and believe). Our hike at Fritz Loven Park last weekend was an unfolding of that process. The trail circled the bottom of a tree-covered, almost snow-bare hill. Warm, crunchy leaves and bright sunshine belied the deep snow and cold temps of the hours ahead.

As we walked along the flatlands by the fast-flowing Stoney Brook, I noticed that most of the trees were young compared to a small number of very large ones. I wondered if this area had flooded. One distinct and eye-catching tree was a large Cottonwood, who would thrive having wet feet, so to speak.

But as we walked up toward a ridge, I then wondered if there had been a fire at one time. Often the tallest, strongest trees can survive a fire that consumes the smaller ones.

It wasn’t until the trail crossed a wide swath of nothingness (and stumps) that I realized the area had been logged. Logging was the predominant industry in northern Minnesota starting in the late 1800’s. Virgin timber was cut in this area around Gull Lake, and a railroad was built in order to transport logs. And in the summer of 1894, Fred Oscar Loven was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Though tourism is now a major industry in the Northwoods region, logging continues. Large wooded areas will reside beside a clean-cut swath or a shaggy area of young saplings or brush that had previously been logged.

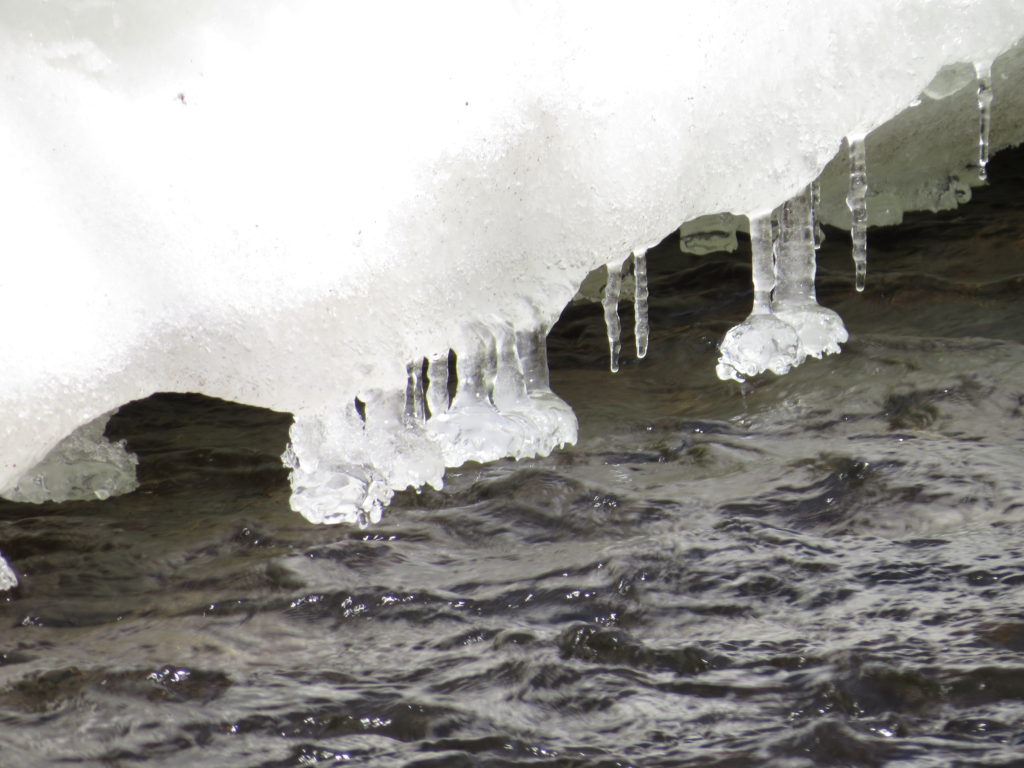

Even through the deep snow, we could see evidence of the destruction of a forest and the life and vibrancy that remained. Dried ferns and wild flowers were visible beacons of the coming Spring when Nature effortlessly performs her miracles of new life.

Our trail through the park had been groomed numerous times throughout the winter for cross-country skiing and snowshoeing. It was packed down and relatively easy to walk on—not too rough and not too icy. The snow pack beyond the trail was also hard enough to walk on, and I asked Chris to use his walking stick to measure the depth of the snow.

It will be a little while until all of it melts…

The trail of Fritz (Fred) Loven’s life is sparse on details (that I could find), but one mention came up from the Pro Football Reference. He played guard one season with the Minneapolis Red Jackets in 1929 at the age of 35. Pro football before the NFL. We do know that Fritz’s trail three years later led him to 80 acres of land west of Nisswa that was his home for 43 years. He lived in a cabin with no electricity, running water, gas, or telephone. The ‘lovable hermit’ (may we all be lovable hermits during this time) didn’t have a car but traveled by foot, snowshoes, or boat.

His greatest contribution, in my opinion, besides his wish for his land to become a park, was that he normally planted 400 trees each year! Most people underestimate or take for granted the true value of a tree. Fritz Loven was a bower billionaire—he lived and worked under the shade of the existing trees and eventually, of the ones he planted—and we are the beneficiaries of his generosity and vision.

Like most ‘big pictures’ of any given situation, the larger perspective of Fritz Loven and his park is complicated. Signage on our hike told us that we were crossing private property at some points, though we didn’t know exactly where that was. Was the logging on the park land or on private property? Did the city need funding from the logging in order to maintain the park? It was sad to see incredible giant Pines and Oaks beside the clear-cut areas. How many trees that Fritz planted were cut down for timber? Who is replanting? Along with the logging, there was also damage from storms, these extreme weather events that are becoming common-place due to climate change. ‘Every situation we confront in life comes from the convergence of many contributing factors.‘ What are the facts? What are the observations? How do we look beyond what we see at any given moment and more importantly, beyond what we believe?

Fritz Loven was the guardian of the beautiful little trout stream, the keeper of the forest, and protector of the trees. He had faith that the trees would grow, the fish would reproduce, and that his vision and work would be a place for people to enjoy decades and decades after he was gone. With the fear and stress of our present coronavirus situation, how do we step back from our limited self-awareness and our limiting self-interest to see the larger perspective? Within our own minds, how do we tamp down the fear in order to see the factors that converged to get us into this situation and the solutions to get us out? We are the guardians of our own bodies and minds, and collectively, we are the guardians of our earth. Faith is how we look beyond what we see. Openness is how we look beyond what we believe. Love is how we show up for ourselves, one another, and for our sustaining Mother Earth. May we be lovable hermits at this time and have all three.