There is something about a prairie in the high months of Summer. The sun is warm, the wind is cooling, and the sky is a partner to the rolling hills of waving grasses. It’s a great place to roam where the mosquitoes prefer not to tread. There is another insect, however, that will garner your attention—the leaping, jumping, bumping-into-shins antics of August grasshoppers. I find them much easier to ‘take’ than biting, swarming mosquitoes. We found this new prairie after hiking miles of trails through a forest. There were patches of wetlands with cattails and Blue Vervain, and along the trail, we found random boulders of granite that established themselves as a grounding focal point in the swaying vegetation.

The Maple tree forest delivered the news of drought and of the coming change of seasons. Already in mid-August, the signs are there—Summer is waning.

The meeting of sky and prairie is an open invitation to experience freedom.

The restored prairie was relatively new, as the Canada Wild Rye was tall and abundant, its curving seedheads nodding in the breeze. Canada Wild Rye is a native, fast-growing perennial bunchgrass that is used as a ‘nurse’ crop for restored prairies. Nurse crops offer protection for the slower germinating grasses and wildflowers while they develop and get established. Nurse crops can provide erosion control, furnish wind, frost, and sun protection for young seedlings, and suppress weeds. Eventually, as the other grasses and wildflowers become more established, the Rye grass will gradually disappear.

There were other grasses maturing into seedheads—Timothy grass (above) and Sideoats Grama (below).

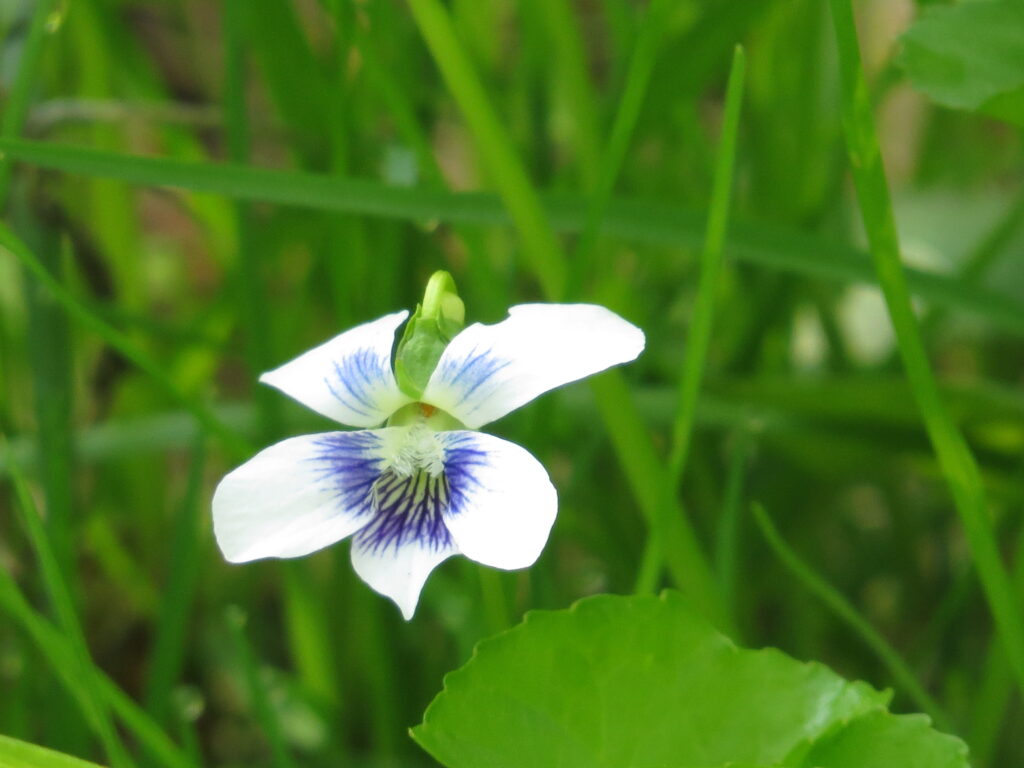

Daisy Fleabane, a bouquet of tiny daisies all in one plant, were scattered throughout the prairie, along with some spent Wild Monarda, Black-eyed Susans, and newly blooming Stiff Goldenrods.

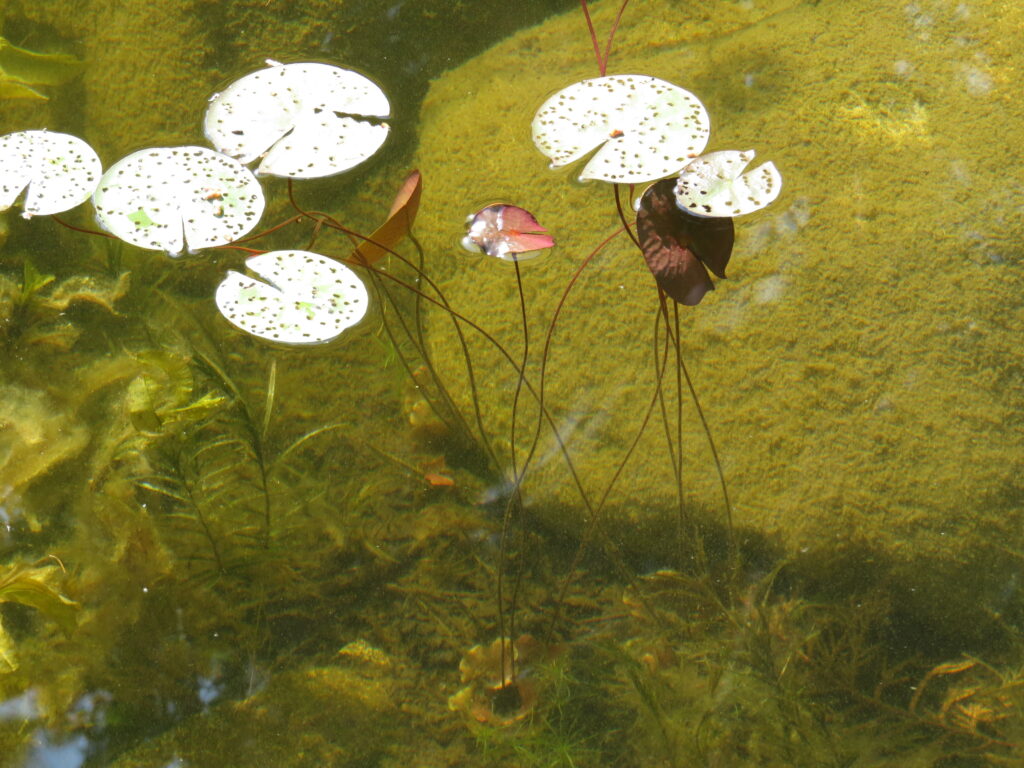

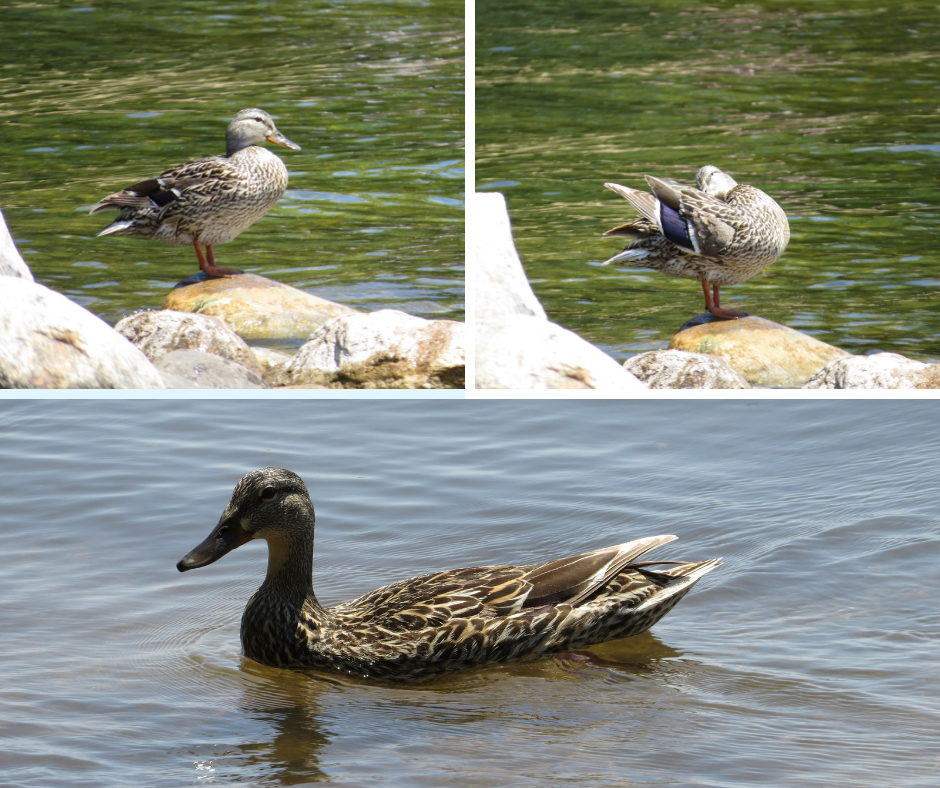

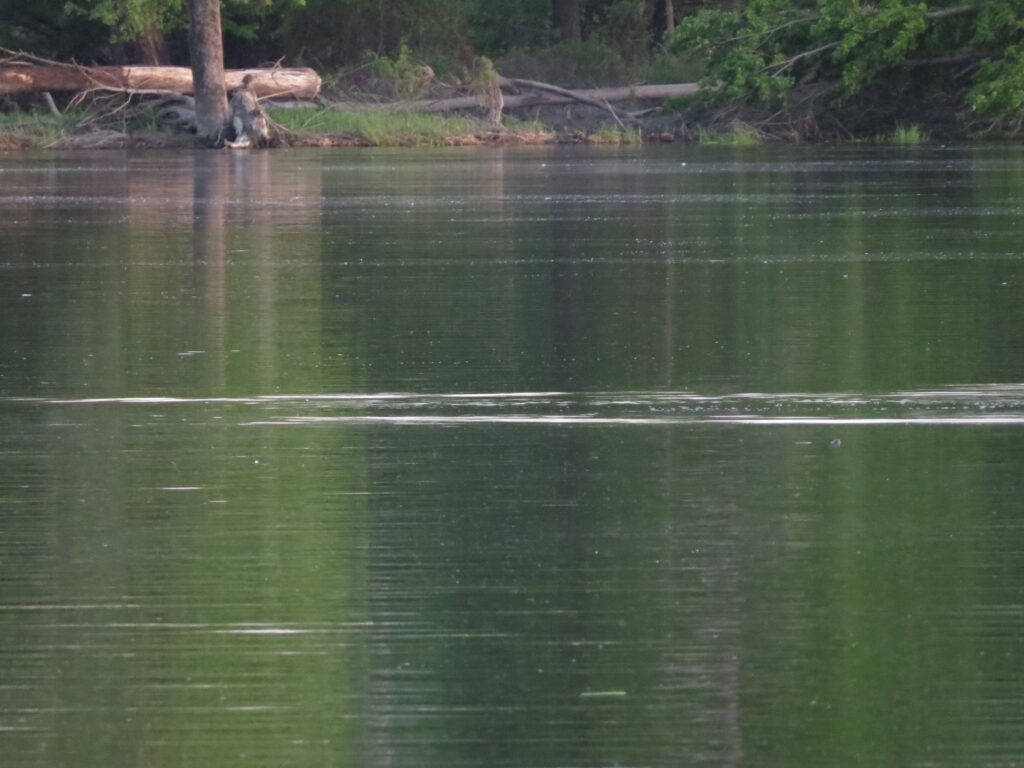

Blue Vervain likes to grow near the wetlands, and the brown, cylindrical flowers of cattails are food for the grasshoppers. Long-legged Leopard frogs leapt across the trail when we neared the lowlands.

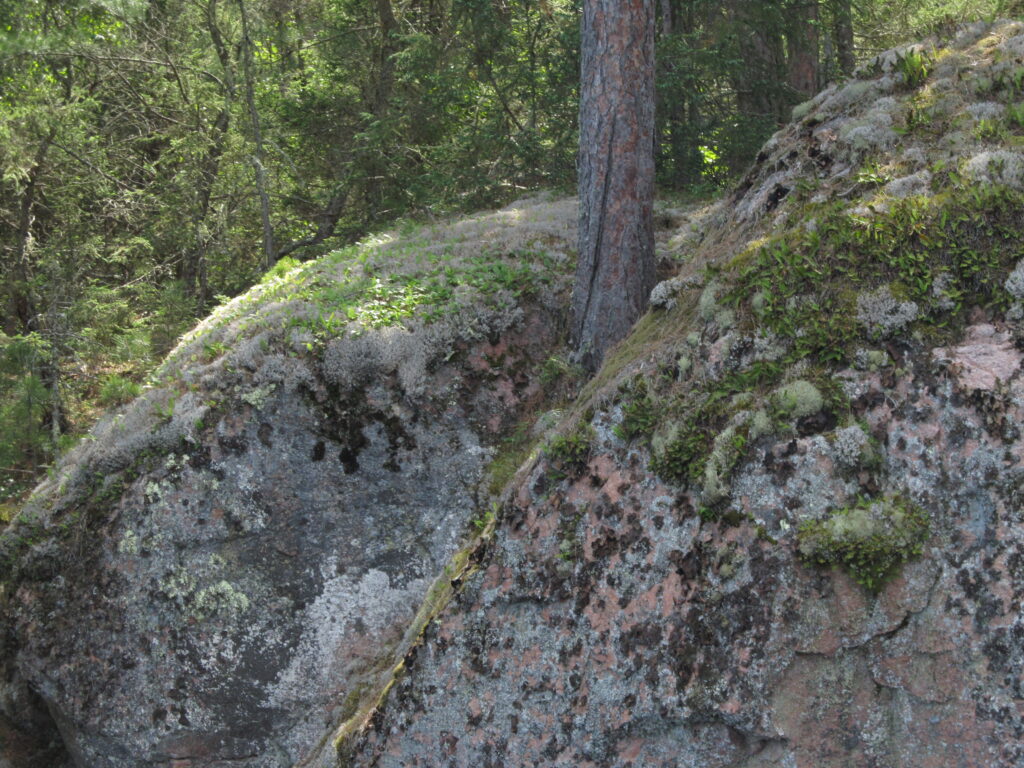

The trail led us back into the woods where Maple seedlings covered the forest floor, pink-leaved asters tried to bloom, and boulders appeared in all their granite glory.

A well-worn and gnawed-upon cow skull lay beside the trail, and burs of every kind were getting ready to hitch a ride on any passers-by.

We passed a bark robe draped over a leaning tree and an unusual wound in a large Maple. The forest glowed green in the dappled sunlight.

Soon we emerged into another prairie area where the blue sky and puffy white clouds once again met the waving grasses. We came to a large granite boulder that had been split with feather and wedges and revealed a hodge-podge of different kinds and colors of granite. We guessed that the area had been explored for granite quarrying but rejected when the stone wasn’t true and uniform.

The prairie grasses, the wetlands that met the grasslands, and the plants and critters that lived there were a part of the all-encompassing title of ‘prairie.’ Each works together, in all their unique ways and means, to bring about the visual beauty of late Summer and the working structure of the prairie ecosystem. It would be mind-boggling to list the benefits the prairie system provides for our world, which include carbon sequestration. It’s not just a pretty place.

Prairies are often overlooked with an impatient ‘there’s nothing there,’ but it requires us to look more closely. It also provides a master class in the evolution of blooming plants throughout the three seasons of growth and decline. I especially appreciate the role of the Canada Wild Rye in the establishment of a new prairie. While nurse crops are used intentionally during prairie restoration, Mother Nature uses nurse plants and trees to protect and promote young seedlings in natural ecosystems. How do we as humans offer protection for our young ones? How do we offer that to the vulnerable people in our society? Close spatial association of the ‘nurse’ has a positive effect on the developing organism, or I would add, to the weak, sick, vulnerable, or wounded. A parent’s role is to be that nurse for our children as they grow and develop—to protect and shelter. But what happens when as adults we are in a vulnerable position—after sickness or surgery, new or old trauma, or loss from these increasingly horrific environmental disasters? We need people and organizations who are ‘nurse’ plants for us while we heal, grow in strength and agency, rebuild, and regain a sense of freedom. There is something about a prairie that pertains to us all.