What happens to your body when someone says, “Hang on tight!”? Usually your hands latch on to something and grip it tightly. Your muscles contract, often throughout your whole body. You ‘brace’ yourself for what’s to come, whether that’s for a physical wild ride or an emotional rollercoaster. There is an element of survival that takes over—your sympathetic nervous system is activated. Adrenaline is released, your pupils dilate, your heart beats faster, and you become hypervigilant. There are plenty of times in life when this response is the prudent thing to do—it can literally save your life.

Chris is back to short hikes—yay!—so we hiked up Hallaway Hill at Maplewood State Park in the western lakes region of Minnesota. The trail zig-zagged through mostly prairie in this part of the 9,200-acre park. Mid-summer wildflowers bloomed among the still-growing green grasses that had begun their blooming, too. Lavender-colored Wild Bergamot or Bee Balm was in all its glory, attracting bees and butterflies with its minty fragrance and tubular flowers.

It was not long before we noticed dragonflies darting around above the plants. It was a breezy day, and I noticed a colorful dragonfly holding on to a dried flower stalk. I thought to myself he must be hanging on for dear life in this wind with his three pairs of legs! Halloween Pennant Dragonflies (isn’t that a great name?!) alight and fly in a different way from most other dragonflies—they have a fluttery flight like a butterfly.

The wooly purple coats of Purple Prairie Clover are wrapped around the gray thimble head of the spikey flowers, belying the typical flower of the Pea family. But like most members of the Pea family, Prairie Clover can increase soil fertility by capturing nitrogen from the air and transferring it to the soil.

More and more of the Halloween Pennant Dragonflies were hanging on to grasses and dried flower stalks, some right by the trail. As I looked more closely at them, it seemed like they were very comfortable on their precarious-looking perches.

Black-eyed Susans brighten the prairie with their cheery ray flowers, and their seeds are favored food for Goldfinches and House Finches.

A larger, more traditional dragonfly with its black and silvery transparent wings is named Widow Skimmer. The male has a long powder blue abdomen and is thus named because he leaves (or widows) the female by herself when she lays her eggs just under the surface of the water. Other male dragonflies will fly with the female while she lays her eggs.

A large, crater-like mushroom captured rainwater and became a ‘watering hole’ for insects and small animals.

The coloring and veins of the dragonfly’s wings create intricate patterns, and their large compound eyes see 200 images per second with nearly 80% of their brain being dedicated to sight! They have specialized spines on their legs used as an ‘eyebrush’ to clean the surface of their compound eyes.

In our northern climate, the growing season is condensed into a relatively short amount of time, so fruit and seed development happens quickly. Signs of decline are already noticeable in the later part of July.

Again, like I noted in my last post, the Monarchs are few and far between anymore. In all the prairie we walked through, we only saw one Monarch. It was perched on its host plant—where eggs are laid and where the caterpillars eat and grow—the Common Milkweed.

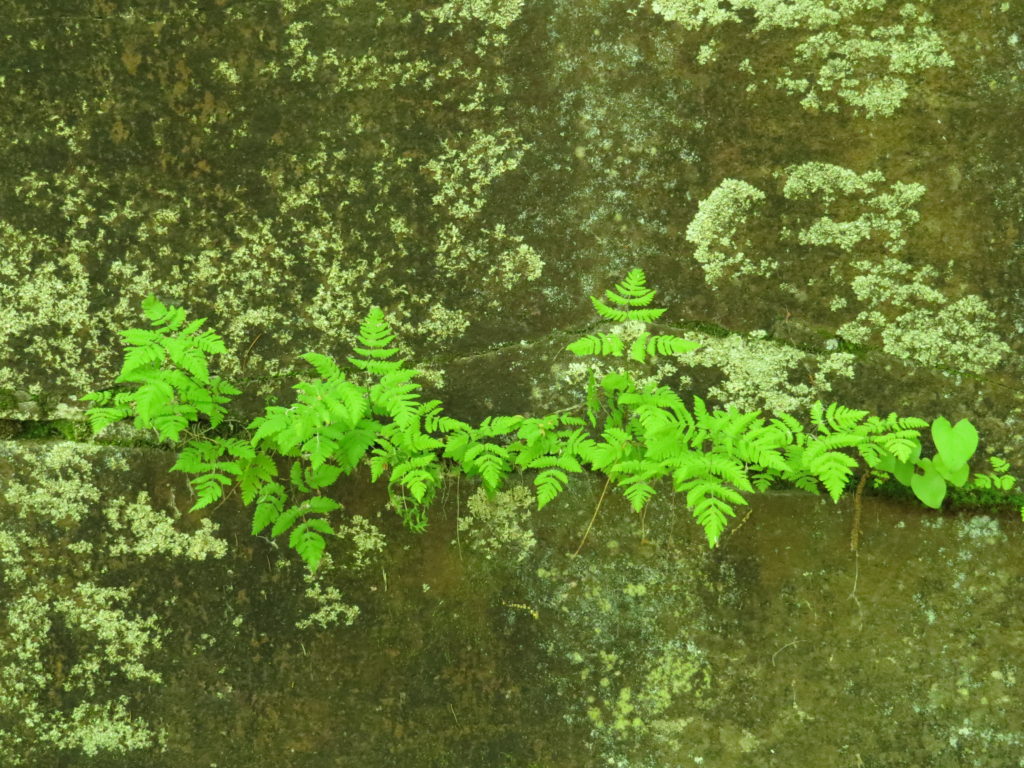

Pointed-leaf Tick-trefoil (Beggar’s Lice) is a woodland plant with pretty pink flowers on long stalks that produce sticky seed pods that hang on to fur or clothing of passers-by.

The silvery-gray color of Artemisia complements all the other prairie wildflowers and grasses.

I was surprised to see a whole Artemisia plant covered in bugs! The black creatures (Black Vine Weevils?) look like the ones who have invaded our house in the last month, and the big, black ants must be getting some sort of nutrition from them.

We ascended to the top of Hallaway Hill, once a popular ski hill in the 1950’s and ’60’s, even after the State Park was established in 1963. 196 vertical feet above Lida Lake gave us a view of the many lakes, the rolling Maple-Leaf hills, and of the storm clouds that were gathering to the west.

Dragonflies spend most of their life in the aquatic nymph stage—the larger ones from three to five years—but only live as an adult dragonfly for five weeks or less, some only for a few days. Their ‘flying’ days are limited.

Hanging on tightly is a way for us to survive—physically and emotionally. In fact, in our young years, it is a reflexive act to connect us with our caregivers for all of our dependent needs. When resources are scarce—food, shelter, safety, and love—we tend to hold on more tightly, even when doing so doesn’t get us those things we need and desire. But as a child and young adult, we don’t know any other way to do it. But what of the fleeting adult life of the dragonfly? The Halloween Pennants were hanging on lightly—not clenched but attached, not contracted but relaxed, not grasping but flowing. They embodied freedom—like an eagle soaring in the wind, like a feather floating through the air, like a leaf drifting on the water. Is it the culmination of their reproductive life that allows them to live out whatever days are left with such freedom? Or is it just a ‘mammalian’ thing to hold on so tightly? We can learn from the dragonflies. We can mature into hanging on lightly. We can brush the cobwebs from our eyes. We can be attached and relaxed. We can live day by each wonderous day, confident in our ability to rest when we need to and fly when we can.