The pandemic birthed the idea. We were having weekly Zoom meetings with some of our kids in the winter of the Winter. Our extroverted daughter Emily was struggling with the isolation and the unknown, undetermined future. She wondered how I could seem so happy in the midst of it all. (Introvert advantage.) She reminded us again and again, ‘We-all aren’t getting any younger.” Her desire for movement, planning, connection, action, and excitement was palpable. I knew how important it was for her to have something to look forward to, and her ‘not getting any younger’ statement hit home with me…so I said, “Why don’t we plan a summer trip to the Boundary Waters?” And the anticipation began.

Anticipation includes preparation, expectation, eagerness, planning, and excitement about something that is going to happen. For me, anticipating this trip into the Boundary Waters also included apprehension, doubts, and a good dose of the big, boogeyman F-word—Fear. While Emily and Aaron had both been guides for many summers preparing for and taking people into the Boundary Waters, this trip would be my first time…. And I don’t swim. And I’m kind of scared of deep water. And I’m afraid of tipping the canoe…and losing my glasses…and not keeping up…and, well, the list goes on. But plans were made, equipment acquired, plane tickets from Texas reserved, BWCA (Boundary Waters Canoe Area) permit obtained, menu planned, food bought, etc., etc. On August 14th, we headed north.

We stayed two nights at KoWaKan, the camp the kids worked at during their college years. We did our last minute shopping (and eating) in Ely and spent time relaxing in the sun and beauty of the northwoods.

We talked about our goals (fishing was high on the list) and concerns. My concern was waves and how to navigate them, so Aaron hopped into a canoe with me on that very windy day, and we practiced.

By evening, the last minute packing was underway, and the non-essentials were stashed in the vehicles for our return. The anticipation was building.

There’s a fine line between excitement and nervousness. As the packs and canoes were loaded on the cars the next morning, I crossed that line. My stomach began to feel ill. I took a few trips to the outhouse. Tears welled up in my eyes. My steps slowed. Now that we were ready to go, I was not at all sure I could do this.

Chris, Emily, and the others gave reassurance that they would help me and take good care of me. I trusted their experience and their words. Deep breaths. We drove to Moose Lake entry point, unloaded the three canoes, five packs, and fishing poles, and we were off on our BWCA adventure!

Fishing began right away—for the humans and the eagles that chattered from the trees alongside the lake.

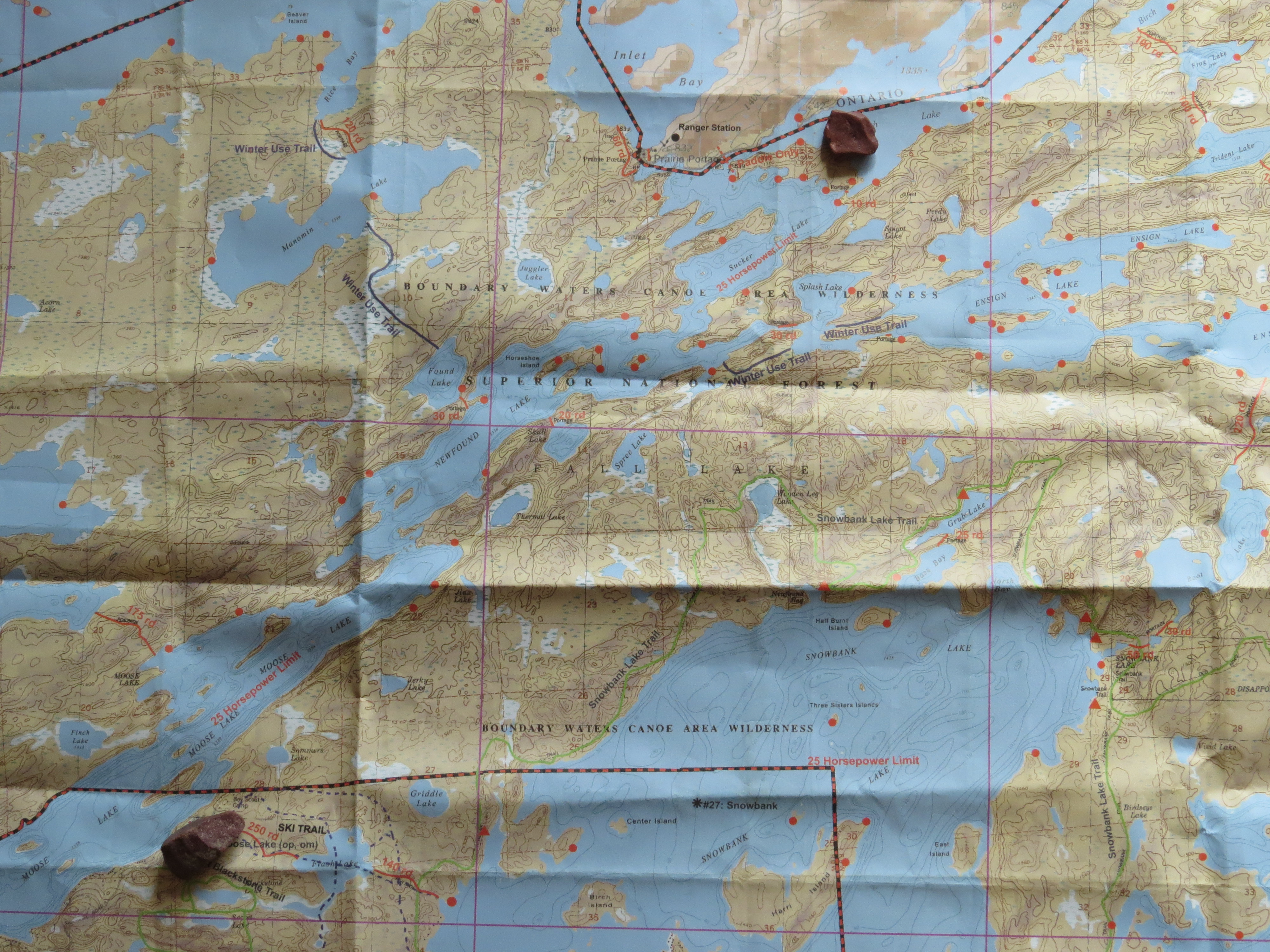

In the months prior to our trip, I had a BWCA map laid out on a bed, and I looked at it every morning. I had no idea at first how far we would go, so I concentrated on Moose Lake where our entry point was and hoped we could get to Horseshoe Island in Newfound Lake, the lake after Moose.

Little did I know at the time that we would be eating our lunch on the first day on Horseshoe Island! It’s strange not knowing the time at any given time of the day. We looked to the sun and our stomachs for clues, but as the days went by, it mattered less and less what the actual time was since it had no bearing on our day. But it was hard to let that time-structure go.

Food preparation was planned and executed by Emily who had done the same process for numerous groups over three summers. She made a menu, we bought the food, she measured it out, bagged it up, and labeled everything. All the food has to be carried in and contained in ‘bear barrels’—plastic barrels with metal closures that protect the food from bears. Since it was a drought year, and wildlife were hungrier than usual, the bear barrels also were required to be hung in trees at night and during the day when mealtime was over.

She had different stuff sacks for breakfast, lunch, and dinner to help organize the barrels. As plastic food bags emptied, they were used for trash, as it is required to carry out all trash. (Which has to go back into the barrels, so it doesn’t attract bears.) Lunches were bagels or pitas, summer sausage, cheese, or peanut butter and jelly. We had one apple each for the week so could choose which day we wanted it. Carrots were our ‘fresh’ vegetables. A handful of trail mix or a homemade granola bar were for dessert or a needed snack.

After lunch we paddled through Sucker Lake until we reached…Canada! We turned to Birch Lake where the low-horsepower motor boats were no longer allowed as they were on Moose, Newfound, and Sucker Lakes.

We paddled with Canada on our left and the United States on our right until we found a campsite on a peninsula that was hanging by a five-rod portage to the mainland. The almost-island campsite was our home for the night.

We unloaded the canoes, set up tents and hammocks, and hung the bear barrels. The fishermen got serious about fishing. The nappers got serious about napping.

The hazy sky of afternoon turned smokier—we could smell it, and the smoke seemed to settle on the water. Because of the drought and Canadian wildfires, there has been a fire ban in the BWCA and most of northern Minnesota. So no campfires for us or anyone. We cooked over a small white gas backpacking stove—our first supper was macaroni and cheese with polish sausages. So good! The largest fish of the trip was caught by our son-in-law Shawn just as evening settled around us. The feisty 30-inch Northern was the one who got away before a picture could be taken—but the excitement of the ones who saw him will stay with us.

We traveled for about eight miles this first day with no portages (as we determined by the map and key after we returned from our trip.) I was getting used to the water and waves. The process was intriguing, the landscape incredibly beautiful, and the companionship of our family comforting.

Because of the drought, there were not many wildflowers blooming, but down by the water in a little boggy area beside our tent, the showy Jewelweed brightened up the dry and dusty landscape. It’s a native plant of the Impatiens genus whose sap from the watery stems has been used by Native Americans to relieve pain and itching from hives, poison ivy, and insect bites. A jewel to look at and a jewel for relief.

My anticipation of our Boundary Waters trip was like the Jewelweed—part jewel and part weed. I loved the excitement and planning of it over months of otherwise difficult times of pandemic and political unrest and uncertainty. It is a priceless gemstone to engage with adult children in a common love and endeavor. But there were definitely weedy things about it—even though my decision to suggest the trip in the first place took much thought and can-do self-encouragement, I still struggled with my fears when the time actually came. If only our fears could be plucked out like weeds and tossed into the compost pile. But they reside with us until they are respectfully encountered and challenged. As I stared up at the stars in our unflyed tent, listening to the calming, flute-like calls of Loons and hoping for a breeze on the stuffy, smokey night, I decided that it had been a pretty great first day.

This is the first post in a series of five that chronicles my experience of five days in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA). It is best to read the whole series from the beginning (Anticipation) in order to understand certain things I refer to in my other posts.